Title: Grothenn, Henry

Source text: Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes, United States Army, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. (1861–65.), Part 1, Volume 2 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1870), 545.

Civil War Washington ID: med.d1e19886

TEI/XML: med.d1e19886.xml

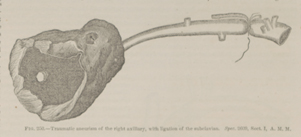

CASE 21.—Sergeant Henry Grothenn, Co. K, 5th United States Cavalry, aged 28 years, was admitted into the McClellan Hospital, Philadelphia, June 23d, 1863, from Lincoln Hospital, Washington, with an aneurism of the right axillary artery, the result of a gunshot wound received at Beverly Ford, Virginia, June 9th, 1863. The ball had passed in on the anterior part of the arm, near the shoulder-joint, and was cut out at Lincoln Hospital an inch below the interior angle of the scapula. In a report of the case in the American Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. XLVII, p. 128, N. S., Acting Assistant Surgeon Isaac Norris says: "When I took charge of the ward, on July 26th, the patient was absent. He returned on the 28th, and after making a careful examination of the arm, the true nature of the disease became manifest, as the pulsation of the tumor at that time about the size of a large horse-chestnut was very apparent, and, upon auscultation, the aneurismal thrill could be distinctly heard, corresponding with the contraction of the left ventricle of the heart. My predecessor had had made an apparatus composed of a compress of lead with screws so arranged that by tightening them any amount of pressure desired could be placed upon the part. The apparatus was adjusted, but after a trial of some thirty hours, it was abandoned on account of the pain it gave the patient, and a padded bandage was substituted, in the faint hope that it might be of use. This was worn for nearly ten days, but it was finally left off, and the treatment was reduced to keeping the arm, as nearly as possible, at perfect rest. On the 16th of August last, the aneurism became much larger, and from the pressure upon the axillary plexus of nerves, caused him great pain. The following evening it was decided to operate and tie the subclavian, despite the hazard attending it. The aneurism broke, unfortunately, early the next morning, before the operation could be performed, and the patient lost from thirty to forty ounces of blood. The hæmorrhage finally ceased of its own accord, but he was so weakened and exhausted from the great loss he had sustained, that it was the opinion of the medical staff of the hospital, upon consultation, that, if anything was attempted then, he would die under the operation, and that his life might be prolonged for a few hours more by keeping up digital compression upon the artery. This was accordingly done, and the assistants appointed, relieved each other every hour or two, until the arrival of Surgeon R. H. Coolidge, medical inspector of the Army, on a chance visit to the hospital, who at once became interested in the case, and thought the subclavian should be tied without delay; the temporary absence of Dr. Taylor, the surgeon in charge, being the objection to its performance. As the patient seemed to be rallying each hour, Dr. Coolidge decided to return to the hospital in the afternoon, and operate, if no objection then existed. Upon his return, the hæmorrhage again having commenced, he proceeded to ligate the subclavian in the third part of its course. I here give the account of the operation as furnished by the Doctor: 'The patient came easily under the influence of the chloroform, and the operation was performed carefully and deliberately. The loss of blood amounted to a few drops only, hæmorrhage from the aneurism having been completely arrested by a tourniquet. Chloroform was not administered after the operation began. The artery, on being exposed, was found closer to the brachial plexus than usual, and it was also quite deeply seated, the patient being a large muscular man. An armed artery needle having been passed beneath the vessel from below upward and outward and withdrawn, it was found by the operator, and his assistants also, that the inferior cord of the brachial plexus was included in the ligature, a result attributed in part to the want of sufficient curve in the needle. Another one, having a more abrupt curve, being armed and passed beneath the artery, it was elevated by the first ligature, and care taken to exclude the nerve above mentioned. The first ligature was then withdrawn, and several of the medical officers present, having examined the parts, and satisfied themselves that nothing but the artery was embraced in the ligature, the knot was tied, the lips of the incision drawn together, and the patient placed in bed.' Everything seemed to do well until about eight o'clock P. M., when the patient complained of considerable pain in the region of the wound. Morphia was given to him freely, and repeated the following hour, but without the effect of quieting him. The patient, from that time, grew rapidly worse, suffering with great dyspnœa, and at midnight expired, six hours after the operation. The post-mortem revealed the unexpected fact that a nerve of considerable size, lying immediately posterior to the artery, had been included in the ligature despite the care that had been taken to prevent it. It is to be regretted that this nerve was not traced to its origin and termination; all that can now be said, is that it was followed as a single cord down to and upon the posterior wall of the aneurism. It was certainly neither of the two cords of the brachial plexus, and its situation was, beyond doubt, abnormal, as the nerve included in the ligature was directly opposite the knot, and cannot be seen when the artery was placed in its proper position. It is scarcely necessary to add that no writer on anatomy has described such a nerve, nor has any dissection on record shown the existence of one, previous to this. At the time the ligature was tied, the patient was but slightly under the influence of chloroform, and no pain was manifested until several hours afterwards. The preparation is an exceedingly instructive one, the aneurismal sac being very large, and the course of the artery well shown. The infiltration of blood also into the surrounding cellular tissue was very great." The specimen, consisting of the aneurismal sac and the subclavian, with a ligature on the third portion, is represented in the accompanying wood-cut (FIG. 250.) It was contributed, with the notes of the case, as subsequently published by Acting Assistant Surgeon Isaac Norris, jr.

FIG. 250.—Traumatic aneurism of the right axillary, with ligation of the subclavian. Spec. 2609, Sect. I, A. M. M.

FIG. 250.—Traumatic aneurism of the right axillary, with ligation of the subclavian. Spec. 2609, Sect. I, A. M. M.