Military Hospitals in the Department of Washington

When a Baltimore mob wounded some of the first recruits on their way to Washington DC in May 1861, several were cared for on the spot, while others were transported to the nation's capital. In the face of the war's first casualties, the military co-opted space in the Washington Infirmary, the only building in the city devoted to general medical care, and it became—at the stroke of a pen—the first military hospital established in the Civil War.1

The Washington Infirmary was typical of the hospitals that graced antebellum cities large enough to have civic support for a place where the deserving sick poor could receive free or very inexpensive medical aid. Washington, like other American communities, had two other institutions where doctors dispensed medical treatment: the poor house, or almshouse, where the city sent indigent citizens and had doctors take care of basic medical needs, and the local insane asylum (St. Elizabeth's), where the city sent the insane poor who could not be managed in their homes or at the almshouse. The county funded these institutions through taxes, while citizens funded the Infirmary through charitable donations, although it may also have received county or city funds for treating the local poor. Because prewar charity hospitals were devoted to the poor and were places of last resort for those who had no friends or family capable of supporting them through their illnesses or injuries, no respectable citizen wanted to end up in one. Doctors served their paying patients in the patients' homes, even for those who could not pay very much, and so few practitioners had spent any time in hospital wards at all by 1861. Indeed, the doctors who attended patients in the Washington Infirmary were the select few who ran the medical faculty at Columbian College and used the Infirmary for clinical instruction for their students. Such arrangements, typical for fledgling medical schools, suited both the needs of the poor and the needs of medical education.2

Military hospitals had their own historical trajectory that shaped their structures and management at the outset of the Civil War. Formed in 1775 to deal with the sick and wounded of the Continental army, the army's medical department and hospital system evolved through decades of confusing and sometimes contradictory enabling legislation. Since the main duty of the military after the War of 1812 had been to deal with conflicts on the frontier and with Mexico, the army organized its efforts around forts and their garrisons. Surgeons were assigned to these posts, rather than to regiments, and managed the sick and wounded in post, rather than field, hospitals, except during the large-scale engagements of the war with Mexico from 1846 to 1848. Then the traditional pattern of medical care for sick and wounded troops on the move quickly reemerged: field hospitals dealt with immediate casualties and then sent the wounded to general hospitals that the army established in large civilian buildings at strategic sites.3 In practice, then, a military general hospital was not a specific type of building but a type of organization headed by a medical officer. This implicit definition served the army well during the Civil War, when hospitals had to be created at a moment's notice.4 A rising tide of medical opinion, however, emphasized the fact that hospitals needed to be specially designed to optimize the free flow of air throughout all the wards to dispel air tainted by the sick and wounded. Florence Nightingale famously attributed the high death rate of British soldiers during the Crimean War to, among other things, lack of proper ventilation around their bodies.5

The tension between the military hospital as an organization that flowed through temporary quarters as needed and the military hospital as a structure purpose-built to maximize the well-being of the sick and wounded (and their caretakers) inevitably shaped the story of the hospitals strewn across Washington and its environs.6 This tension, too, was but a subset of the much larger stresses of a war fought with a volunteer (temporary) and regular (purpose-built) military, which had the near impossible task of trying to plan for casualties as well as managing the men and material needed to defend the capital and fight the battles. In 1862, at the urging of medical officers and the United States Sanitary Commission, the military designed and built five pavilion style hospitals in the capital that embodied the most up-to-date principles of ward ventilation and provided 4,611 beds by February 1863.7 Announcing that a hospital was to be built on "vacant lots to the east of the Capitol," for example, the National Republican assured its readers that it was "to be constructed with every regard to the requirements of sanitary science."8 But then the government stopped. For the rest of the war, two-thirds (more or less) of the hospital beds in Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria stayed in churches, schools, houses, tents, and barracks, although, to be fair, the latter were improved over time.9 The army certainly could have built more hospitals in Washington, but not, perhaps, without announcing that the generals anticipated a regular flow of high numbers of casualties and, of course, spending too much money.10 The hoped-for short-term use of buildings designed for normal civilian life, even when that "short-term" lasted for nearly five years, emphasized that the war would not, could not, last long.

The pavilion style hospitals—notably Armory Square— became flagship institutions. From its earliest days, Armory Square had a strong reputation for order and amenities. Louisa May Alcott, in her Hospital Sketches (1863), hoped very much that she would be assigned there when she volunteered for war nursing in 1862. Some of the most famous photographs of Civil War hospitals are those of wards in Armory Square, with calm-faced men in uniform in sunny, open spaces, next to beds covered in snowy white linens. This is exactly what people wanted to see and to believe about the care of the war sick and wounded.11 The Armory Square Hospital Gazette, published from January 1864 to January 1865—through the worst year for war casualties in DC—printed inspiring poetry, positive news, and spritely accounts of hospital life, creating for its readers in (and perhaps more importantly, out of) the hospital a constant impression of noble endurance and the best in medical attention from nurses, orderlies, and surgeons. The daily newspapers, as well, unfailingly published nothing but positive accounts of Armory Square and its head surgeon, Dr. William Bliss.12

As important as the pavilion style hospitals were as testaments to the military's good intentions toward the war's casualties, the press found reasons to praise several of the hospitals converted from civilian buildings and barracks. In the first months of the war in particular, when the Union Hotel, Miss English's Seminary, and the former Brazilian embassy were converted, much attention was given to their suitability for the sick and wounded. At least as far as newspaper reports indicate, in August 1861 the Union Hotel had "arrangements for ventilation quite as good as in the buildings of the same class anywhere," while Miss English's Seminary not only had "high and airy rooms" but it was also "in one of the most healthy, quiet and pleasant neighborhoods in Georgetown."13 Even after the pavilion style hospitals opened, news writers lauded the Campbell (former barracks), the Douglas (former residences), and the hospital at Columbian College. Indeed, the Campbell was described as a "spacious and charming retreat," which had encouraged "a spirit of enterprise" in its neighborhood with the "building of hundreds of neat and comfortable dwellings, with a fair proportion of shops and places of business."14

Of course, not all of the civilian buildings that the military used could be publicly praised for their virtues as hospitals. The very lack of press commentary on the healthful atmospheres of churches, for instance, or the faint praise given to the use of the Patent Office as an 800-bed sick room (it had a "most excellent cooking department"), suggests that Washington's citizens knew very well that the army had to use what it could get.15 The military turned to churches in the summer of 1862, in anticipation of the casualties expected from the Peninsula campaign, when only two of the new pavilion style hospitals were ready for occupation. Some churches were literally taken with the authority of the secretary of war. As Ernest Furgurson recounts in his Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War, irritation with pro-South ministers lead to the appropriation of three Episcopal churches: the Ascension, Trinity (DC), and Christ Church, all of which opened as hospitals on June 20 and 21.16 At the same time, some congregations, as good Christians, volunteered their buildings to demonstrate their support for the sick and wounded. The trustees of the Union Chapel, for instance, offered the secretary of war both their chapel and "the services of members of the Church" in June 1862. The army accepted and used it from July to December of that year.17

To the extent that such volunteering became the thing to do in the summer of 1862, it briefly sparked some religious posturing. In the press announcement that the Seventh Presbyterian Church had offered its building to the cause, for example, the author noted that "a large number of citizens are enquiring why it is that the Catholic churches do not exhibit the same patriotism, humanity and true religious principles, by offering one or more of their churches."18 The secretary of war, perhaps in a spirit of ecumenical fairness, did decide to take at least one Catholic church that fall. The priest and parishioners of St. Aloysius, who objected vehemently that the conversion would desecrate their building, rallied together and built a barracks on empty grounds nearby as a substitute.19 Which of the other churches used as hospitals were volunteered, taken, or spared based on the degree of their ministers' patriotism or Christian spirit remains a question to be explored. To the relief of their congregations, the use of churches was relatively short, as most of them had their patients transferred to nonreligious buildings by February 1863. In the end, only eighteen of the seventy-nine churches in Alexandria, Georgetown, and Washington served as hospitals.20

Although the discussion so far indicates that the city's newspapers tried to present hospitals in a positive light, not all of the news was so uplifting, particularly early in the war. Soldiers who did not like hospital conditions—especially the quality and quantity of food—wrote regularly to the newspapers, to the secretary of war, the secretary of the interior, the surgeon general, officials of their state relief organizations, and likely a number of other offices with their concerns.21 In February 1862 the National Republican published a telling series, the first article of which was entitled "The Horrors of the Alexandria Hospital." After receiving a complaint from an aggrieved soldier, Col. James Mansfield, who had been appointed by the state of Wisconsin to examine how Wisconsin soldiers were being treated in the capital, investigated conditions at the General Hospital in Alexandria and at the Seminary Hospital in Georgetown. He gathered accounts from a number of patients and made their letters available to the newspaper reporter. Together they tell a damning tale: soldiers denied food, made to eat out of the slop bucket, confined to a room on bread and water, being refused admission, and held in the hospital against their will. A response to these charges appeared the next day and, a month later, the report from the court of inquiry that the army had held to examine the complaints.

While the court acknowledged some problems, such as a load of very poor flour once making bread scarce, the rest of the issues were dismissed for lack of proper evidence of abuse. The soldiers denied food? Some were on a reduced diet by order of the surgeon dealing with their conditions. If they ate out of the slop bucket, that was their poor decision making at work. Confined to a room? Convalescent patients were given day passes out of the hospital and, more often than not, returned quite drunk and unruly. Proper punishment was confinement. Being refused admission? Of course, sick soldiers could not just wander in off the street—they had to be referred by their regimental surgeons. Held in the hospital against their will? Certainly. It was the job of the surgeon to determine fitness to return to duty. Any soldiers who thought that the doctor could discharge them from the army, and was mean to refuse to do so, were corrected on the rules: only commanding officers, not doctors, could sign discharge papers.22

Investigators, whether appointed by states to look after their own soldiers, formed by larger civilian welfare groups, or charged by Congress and the surgeon general, regularly took stock of hospital conditions and reported on them. Certainly some abuses occurred, including lack of food, unjustified confinements, indifference from surgeons and nurses, and inattention to proper cleanliness. Those described by Hannah Ropes, the matron at the Union Hotel Hospital from July 1862 to January 1863, in her unpublished letters and diary, for instance, confirm that the District's hospitals had their share of corrupt administrators and lax staff.23 Given the access that inspectors and other visitors had to the hospitals, however, along with individual soldiers' willingness to complain to higher authorities, large-scale deprivations and ongoing, deliberate cruelty could not have been tolerated for long. The vision of "comfortless hospitals, where lie the brave defenders of our Union, parched with fever or racked with pain; exposed sometimes to the brutalities of despotic surgeons or left unattended by drunken nurses," nevertheless persisted in popular imagination and fueled the call for citizens to contribute what they could to easing the suffering soldiers' lots.24

As much as the general hospitals in the District and Alexandria were clearly military institutions, not to be confused with charity hospitals for the poor, the appeal to citizens to give hospitals money, time, food, clothing, and other materials resonated with prewar traditions of charitable support for the unfortunate.25 The large sums and considerable number of volunteer hours donated to the United States Sanitary Commission, the private association endorsed by the government to coordinate medical and other aid to Union soldiers, indicate that citizens knew from the start that the government would not be able to supply its troops with what they needed.26 While the motivation for citizens' help and generosity was ostensibly patriotism and the sense that everyone should sacrifice something for the national good, the emphasis on caring for medical needs tapped into deeper civic rituals. Like charity hospitals, military hospitals largely served the underclasses: privates and noncommissioned officers. Although ranking officers did end up in the general hospitals with enlisted men, the military authorized hospitals that would admit only officers and provided surgeons to attend to officers in their quarters or lodgings.27 Military hospitals also mirrored their civilian counterparts by being locations for the moral and religious uplift of the sick, wounded, and dying. Finally, like charity hospitals, the general hospitals in the District became focal points for civic virtue and civic organization, outlets for the noble sacrifices not only of the soldiers but also of women.

As envisioned by their middle-class founders and supporters, charity hospitals could bring moral regularity, if not religious conversion, to the poor patients within them.28 So, too, could engaged citizens bring middle-class civilization to the sick and wounded in military hospitals. One avenue was music, including the "music to which [the patient] has marched many a weary hour"; its advocates claimed that such music had "a healthful influence." Perhaps more welcome were opportunities for singing, both by the soldiers themselves and by visitors.29 Patients were encouraged to read, and donors gave books, journals, and newspapers to fit up hospital libraries. Bibles and religious tracts were among the gifts, especially those provided by the Christian Commission, itself formed, as the U.S. Sanitary Commission had been, to solicit goods, funds and volunteers in part to aid military and civilian chaplains in the war effort while saving soldiers' souls.30 A library of "good reading matter" rather than that "of doubtful character" was "doing good," claimed the author of a report on the "spiritual and intellectual condition of the patients in Carver Hospital," as were Sunday services and twice weekly prayer meetings.31 At Lincoln Hospital, patients "organized a society known as the McKee Lyceum for self-improvement," which included a speaker invited to lecture on "the Condition of our Country." Lectures, "literary exercises," amateur theatricals, and similar improving events graced the dining halls and wards of Washington's prominent hospitals, particularly in the last two years of the war.32

A major source of moral goodness within the hospitals was, of course, the middle-class women who demanded to be allowed to serve as nurses. Their story has been well told elsewhere.33 Almost by sheer force of personality, the reformer Dorothea Dix convinced the authorities that women should, and would, volunteer to work in general hospitals. She was granted control over which women would be able to do so, and she particularly sought plain women, aged thirty or over, of unimpeachable moral character. As surrogate sisters, mothers, and aunts, female nurses were supposed to evoke the comfort and compassion of home life, itself an idealized vision of domestic virtue. Nurses toiled, but they also sang, read aloud, wrote letters, dried tears, held hands, and prayed with the soldiers.34 As important as their presence was, however, female nurses were always a minority among those who worked in the hospitals on a regular basis, even including the female servants (laundresses, cooks, and scrub women), since convalescent patients were usually tasked with nursing chores.35 Relatively few women who may have wanted to help the sick and wounded could have left their own homes and duties to domesticate general hospitals. But there was still plenty that women could do.

Calls for "the Ladies of Washington" to provide "more attention and many comforts beyond what are ordinarily to be expected in a regular military hospital" began in May 1861, as troops started to arrive in the District and, not surprisingly, sometimes became ill.36 Then came the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861. The capital felt the shock of serious war, as the wounded straggled in on foot and in wagons after the Union defeat. Citizens rallied to provide food, drink, and shelter to the less seriously wounded.37 Conditions during the summer of 1862 were much worse. As casualties from the Peninsula campaign came in over the summer months and churches were made into hospitals, more appeals went out for the "aid and comfort" that only women could provide. "After Government and the Sanitary Commission have done all they can, enough remains for you to do," female readers of the daily papers discovered.38 Mrs. Lincoln's visits to hospitals were duly noted and praised, and she spent money donated by worthy folk on "cooling fruits and other needed comforts" in August. Then came the second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862, when thousands of wounded poured into the city in the first days of September. Again, some of the less badly wounded "were taken in by kind-hearted citizens and well cared for" while the worse off were conveyed to hospitals.39 Civic attention to the hospitals intensified.

Ladies disinclined to actually visit the sick and wounded very often found a suitable outlet in the move to supply hospital patients with all of the home-style trappings of holiday fare. Thanksgiving, Christmas, and the Fourth of July became rallying moments for citizens' generosity, and women's efforts figured prominently in successfully offering lavish dinners. The first Thanksgiving after the Second Battle of Bull Run set the tone, as the newspapers reported on holiday feasts and sermons in all of the hospitals in Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria. Of course, the "ladies of Washington" outdid themselves at Armory Square, where they, together with various relief organizations, offered a "sumptuous dinner" where "everything . . . was neat, tasteful, and appropriate." Other hospitals were the particular care of various organizations and congregations. "The ladies of the Dumbarton street Methodist Church, and other ladies of Georgetown," for example, provided food, "flowers and festoons" for the Methodist Church Hospital. In the hospitals where only the medical staff provided funding for food, public praise was less enthusiastic, even absent. At Finley Hospital, surgeon J. Moses, in response to the reporter's questions, observed that "he hadn't had any dinner himself, and appeared to be very indifferent to the fare of the soldiers."40 A week later, the Daily Morning Chronicle noted that Christmas was approaching and urged citizens not to let any patient go "unnoticed and neglected." The city's aid societies and "the generous ladies of Washington and vicinity" needed to furnish Christmas dinners to all of the sick and wounded, if not through food and time, at least with donations of money.41 To ensure that this was done, the wife of the secretary of the interior, Mrs. Caleb Smith, organized a "great meeting of ladies" during which committees were formed to be in charge of the celebrations at each of the hospitals, including the Finley, where surgeon Moses had been so lax.42

For the rest of the war, newspaper reports on holiday celebrations included notes about the festivities at the District's hospitals, along with accounts of other social events of public interest.43 Surgeon J. H. Baxter organized a "Grand Levee" at Campbell Hospital in 1863, for instance, at which four hundred guests danced and visited the sick and wounded soldiers. "Everyone was happy," the reporter noted, and the visitors found all of the patients "well cared for, and much pleased with the music and general festivities in the neighboring wards."44 When, on October 22, 1864, the city held a "grand torchlight procession . . . in honor of the recent Union victories in Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Maryland," the bands of Finley, Armory Square, and Lincoln, the drum corps from Columbian and Ricord, and doctors and convalescents from each of these hospitals marched in the parade. Each city ward had a delegation, too, as did several state organizations, and members of the Lincoln and Johnson Club held placards rooting for Republicans' reelections. A New York State agent electioneered at Harewood Hospital that month for General McClellan for president, to lukewarm responses, while a crowd over twelve hundred strong gathered at Armory Square to hear speeches on behalf of Lincoln's ticket, with "a large attendance of ladies" and decorations of stars and stripes adorning the hall.45

The District's military hospitals thus wove themselves into the civic life of the capital. Civilian buildings were transformed into places for the sick and wounded. City newspaper reporters reassured inhabitants that the patients were well cared for, but at the same time served as watchdogs for abuses that added to soldiers' sufferings. The military hospitals joined the roster of other good works (such as a newsboys' home and aid for contrabands) that demanded the time, effort, and money of the "ladies of Washington." Women in the District helped to provide the music, good books, festive dinners, even the proximity of dancing couples, to amuse and to improve patients' minds and spirits; those who could not take part in such efforts could read about them in the daily papers.

The sick and wounded became both a literal and a psychological presence for four long years. As news came that armies were moving, "quiet . . . then brooded over us, while anxious hearts waited for the first sound of the coming strife," one reporter wrote in May 1864. That quiet dissipates, and "the turmoil and bustle, the excited crowds, the sickening sights and sounds that ever follow in the train of battle" visit again. The author continued:

As if to impress the horrid realities of war more deeply on our minds, long lines of ambulances moved in mournful procession through the streets, loaded down with suffering weight. Slowly and carefully the wounded have been transported from the landing to the hospitals, awakening in the breasts of thousands of spectators a sympathy that has often found vent in something more substantial than words. We venture to say that the wounded of any army that ever existed never received such tender and unremitting attention as has been afforded our own after their reception in this city. The commodious and splendidly arranged hospitals, which Government has spared nothing to make perfect, have some of them been taxed to their utmost capacity, yet, so far as we have been able to discover, everything has been conducted with the utmost system, and all of the sufferers have met with prompt and faithful care. . . . The Government furnishes everything possible to alleviate the suffering of her wounded soldiers; but the kind offices of benevolence, the little attentions, the cheerful words, so powerful for good to the suffering, these, reader, are yours to afford."46

His words aptly summarize the overall message repeated so often by Washington's newspapers: feel for the thousands of the military's sick and wounded in the city, take comfort in the fact that the government was (almost) perfect in caring for them, but do not take so much comfort that you forget that more is always needed.

As the war had its periods of quiet anticipation and frenetic activity, so too did the number of patients in the general hospitals rise and fall. The number of men in the hospitals mattered, as Washington's citizens certainly learned after the First Battle of Bull Run, when there were not enough hospital beds in the immediate aftermath to hold the wounded. In August 1861 newspaper readers were introduced to hard numbers. For a year, until August 1862, Washington's papers published lists of the District's military hospitals with the number of patients within them, breaking the men out by regiment. This effort began when Senator Henry Rice (MN) introduced a resolution "that the Secretary of War be requested to cause to be published weekly, in each of the newspapers of the city of Washington, the name and location of each public hospital in the District of Columbia, and the number of sick or wounded of the various regiments in the several hospitals."47 He wished this, he explained, because he had "had great difficulty in ascertaining whether there were any sick from the Minnesota regiments within the city, and after I heard that there were, I had the greatest difficulty in finding them."48 If he had problems, then surely other citizens did, too. The secretary of war ordered this to be done, and the Washington Evening Star and then the National Republican duly provided weekly reports that included the total number in each hospital, from which it was possible to sum the number in the District.

For reasons as yet unknown, newspapers ceased publishing this data on August 1, 1862, when the total of sick and wounded soldiers in the general hospitals reached 6,249 men. Newspapers continued to publish directories of the military hospitals in the city, giving their addresses so that visitors could find them, so part of the Senate's resolution remained in force. The United States Sanitary Commission had begun to take on the task of helping civilians track down their loved ones in hospitals and, in November 1862, officially became responsible for maintaining a hospital directory to which people could write for information. Agents from state relief organizations, too, had become responsible for tracking their own soldiers in the hospitals, so perhaps the newspaper reports were no longer seen as vital.49 The press still wrote about the number of men lost and wounded in battles, so sensitivity to public feelings does not seem to be the reason that they ceased giving numbers by regiment in each hospital.50 The military continued to gather the data as well, so the information was there to be had, although what the Surgeon General's Office worked with at this time was sometimes incomplete and late in arriving.51

The data that the army did collect was carefully transcribed into a volume, the Records of the General Hospitals, 1862–66, shortly after the end of the war. The Surgeon General's Office staff tabulated weekly census data for all of the Union's general hospitals by department. The Department of Washington encompassed Alexandria, Georgetown, Washington, and the U.S. General Hospital at Point Lookout, Maryland. (The data from this latter hospital are omitted from the charts and numbers discussed here, as it was clearly well outside the District.)

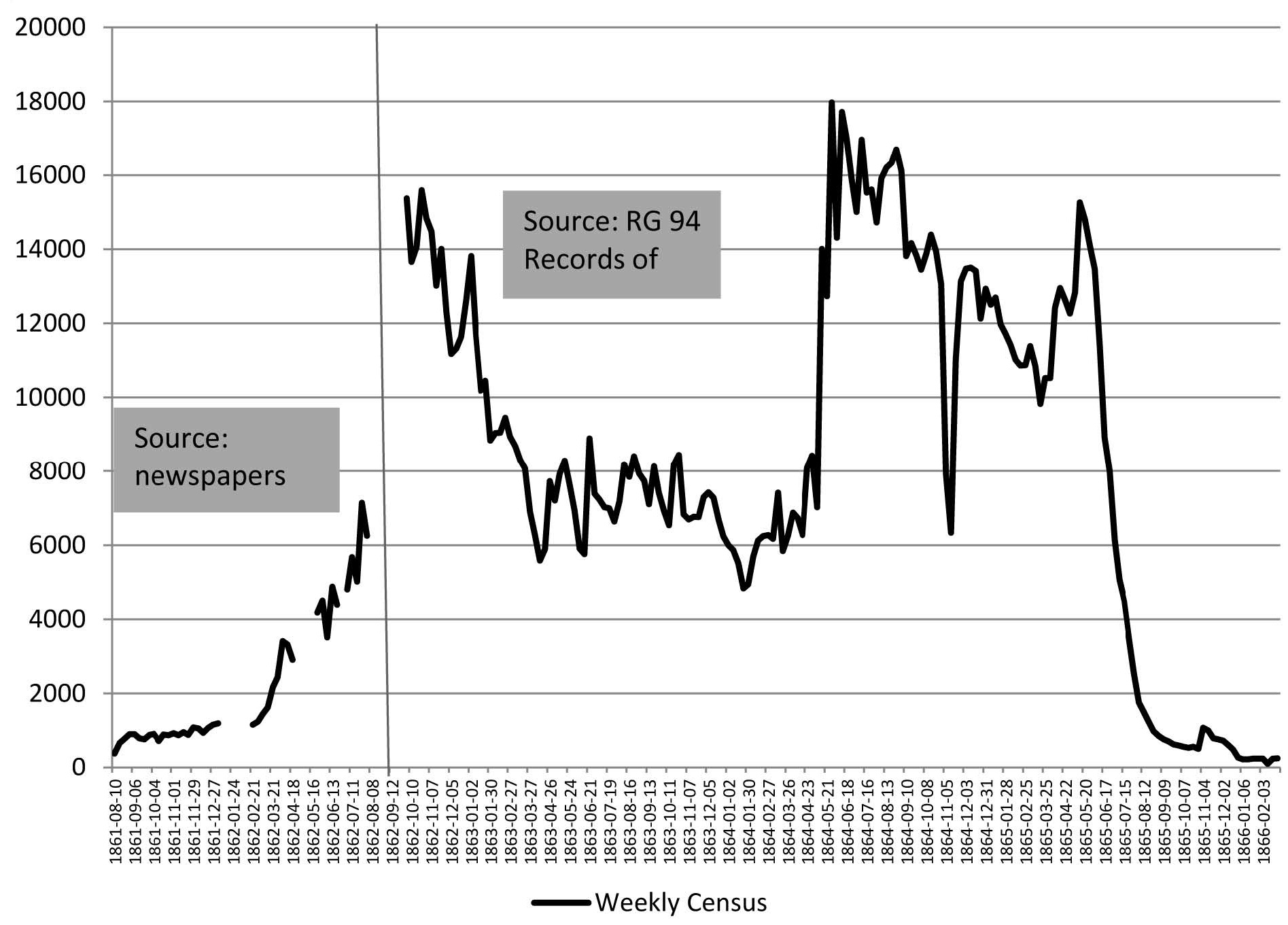

Combining the information culled from newspaper reports and that from the Records of the General Hospitals gives a fairly good idea of the number of soldiers in the District's hospitals from August 1, 1861, to February 2, 1866, as shown in Figure 1. The data are incomplete, not only because newspapers skipped weeks in reporting on hospital populations but also because there are a few blanks in the tables transcribed into the postwar register. These figures, moreover, do not include the numbers of sick and injured in the post hospitals provided for the regiments manning the fortifications around the District.52 The data for the general hospitals are, nevertheless, the best we are likely to ever have, and they give us an important alternative perspective to newspaper accounts and individuals' experiences as recounted in their letters, diaries, and autobiographies.

If the number of patients served at least in part as a visceral measure of the cost of the war for Washingtonians, then September and October 1862 and June through August 1864 were the most expensive and heartrending times. In contrast, the dramatic events of Gettysburg, and the huge losses sustained there, were felt less in Washington and more in Baltimore, New York, and York and Harrisburg in Pennsylvania.53 The jagged line of the chart also reflects the flow of sick and wounded through Washington. As soon as men were well enough to move to hospitals further north or to their home states, they were transported out to Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and other points in the Union. During active fighting, especially, moving those who could be moved to make way for anticipated casualties was one way to minimize the risk of not having enough hospital beds to accommodate disasters.54 Figure 2 reveals that the end of the war was by no means an end to the casualties in the capital, as the sick and wounded from field hospitals and general hospitals in the South were transferred to Washington before being sent home. Hospitals in Washington closed fairly rapidly after mid-May, but it still took months to deal with the 15,000 patients who needed care at that time.

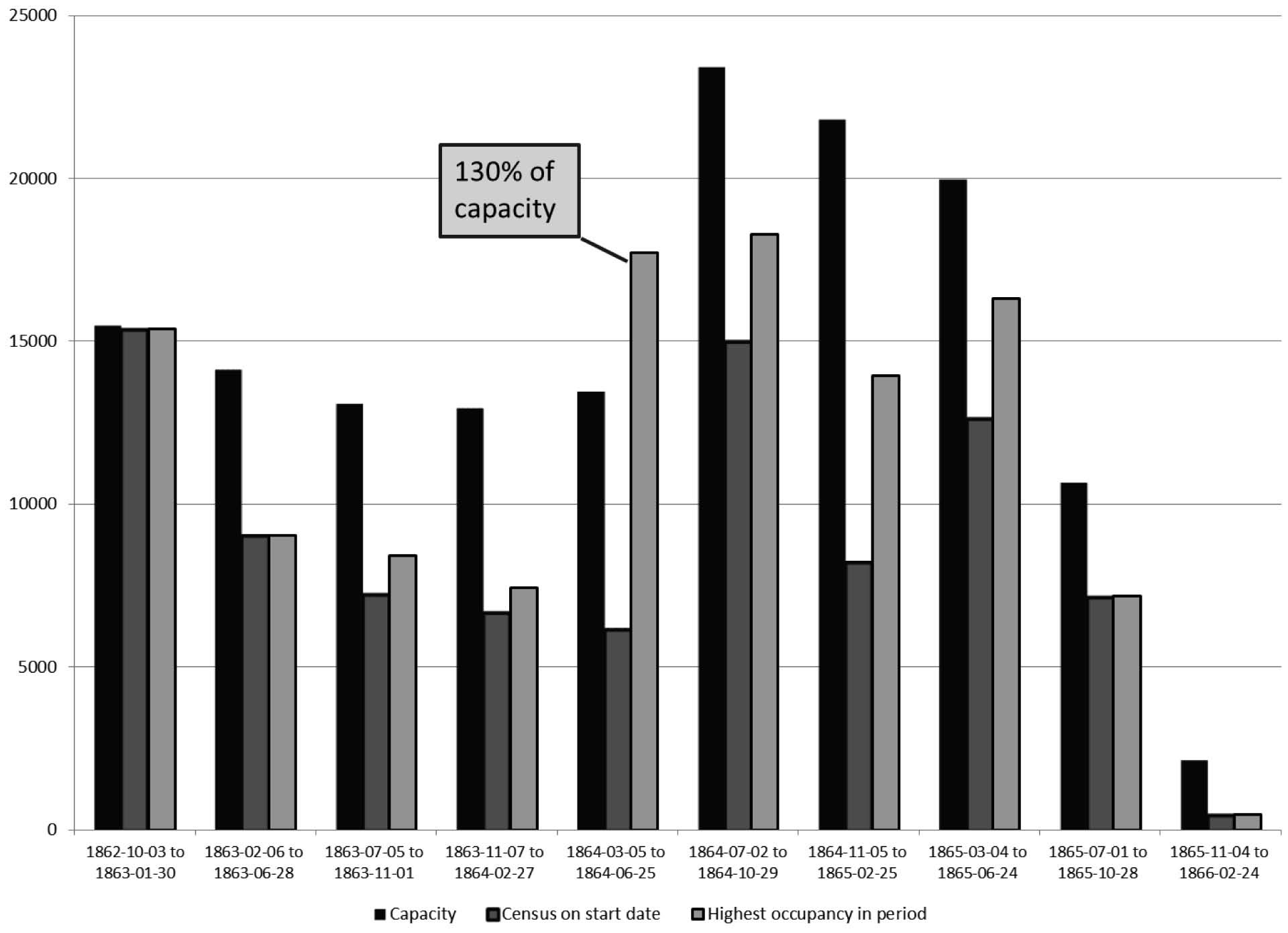

Hospital capacity offers another way to visualize conditions in Washington. The data in the Records of the General Hospitals were organized into tables with four (and, once, five) months of weekly data given across two folio leaves, with the capacity of each hospital listed at the start of each new table. Figure 6.2 displays the capacity, the census on the start date of the table, and the highest occupancy recorded for each period in the register. The Medical Department faced the constant challenge of providing enough hospital beds to serve the military's needs, but not so many that resources were wasted. According to the register, in October 1862 Washington's hospitals were just about full. The Lincoln, the last of the new pavilion hospitals, opened in December, by which time the number of patients had been considerably reduced and churches used as hospitals were being returned to their congregations. Occupancy then ran between 40 and 65 percent, providing a comfortable cushion of empty beds until—not surprisingly—the Battle of the Wilderness and the Battle of Spotsylvania in May 1864, when occupancy soared to 131 percent of the capacity available in early March. The number of patients reached 17,977 on May 28. For this excess, the military was prepared with tents that were quickly raised on the grounds of hospitals that had the space. Between March 5 and July 2, for example, Harewood went from 1,000 to 2,000 beds, Mt. Pleasant went from 390 to 2,000, and Lincoln from 1,240 to 2,575. All told, the number of beds went from 13,481 to 23,434. The Department of Washington was not caught short again for the rest of the war.

Claims about the number of sick and wounded in the capital are scattered throughout both primary and secondary sources, and quite a few are likely to be exaggerations, if the Records of the General Hospitals data are at all reliable. The Daily Morning Chronicle on November 11, 1862, for instance, stated that "the largest number of patients ever congregated at one time in Washington was 28,500."55 The official record for that date shows 13,019, with a 15,488-bed capacity as of October 3. But the fragmentary reports provided in the newspapers never had numbers close to 28,500. Could over 10,000 sick and wounded have been lying in the fort hospitals that surrounded the city? Post hospitals, as regimental units, did not fall under the jurisdiction of the Medical Department of Washington, and the numbers of their sick and wounded were not included in the Records of the General Hospitals. While regimental surgeons certainly reported on the number of sick and wounded in post hospitals as part of their duty to provide commanding officers with information on the active strengths of garrisons, this data was not officially collected in the same way as that for general hospitals. Considering that the number of troops assigned to the Defenses of Washington varied from 18,000 to 30,000 between 1861 and the early fall of 1862, it is highly improbable that 10,000 of them were staying in their post hospitals.56

Walt Whitman, a tireless visitor to the sick and wounded in Washington from the beginning of 1863 to the end of the war, was one of those whose observations have led us, as one Whitman scholar has put it, to believe that "Washington's hospitals were continuously full." In his Memoranda during the War Whitman described the hospitals from August to October 1863 as

all fill'd (as they have been already several times) they contain a population more numerous in itself than the whole of Washington of ten or fifteen years ago. Within sight of the Capitol, as I write, are some fifty or sixty such collections or camps, at times holding fifty to seventy thousand men. . . . Indeed, we can hardly look in any direction but these grim clusters are dotting the beautiful landscape and environs.57

Secondary sources have, unfortunately, repeated claims of the same order of magnitude as Whitman's estimate of fifty to seventy thousand sick and wounded in the capital.58 The fact that the hospitals were neither continuously full, nor filled "several times" over, nor able to hold fifty to seventy thousand sick and wounded soldiers contrasts the vivid impressions that the hospitals left on men like Whitman with the approximation to reality given by surviving military data.

The military's numbers may be the best for understanding the physical stresses that the general hospitals put on Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria as cities united into the Department of Washington, and surrounded by the post hospitals of the Defenses of Washington. The magnitude of food, clothing, labor, and skill required to care for six, ten, or twenty thousand sick and wounded men at a time, the number of wagons needed to transport them to and from hospitals, and the degree of charitable feeling inspired to feast them at Thanksgiving and Christmas can be realistically compared to the demands placed upon the city by its growing population, the influx of contrabands, and the thousands upon thousands of healthy (or healthy enough) soldiers moving through on the way to war. The numbers were substantial, but the military and the city managed them and, at times, even managed them with generosity and civic pride.

Whitman's numbers, however, may be the best for grasping the psychological stresses that the presence of so many sick and wounded brought to the capital. The suffering of ten thousand men could well feel like the suffering of fifty thousand when visiting the wards of a hospital with two thousand beds. The vision of twenty-five hospitals (the number of general hospitals in the wartime District during Whitman's work) could well look like forty or fifty, given their disconcerting presence on a civilian landscape. It may well be that it was the need to remove all traces of the years in which sick, wounded, and dying soldiers were a constant presence that led to the hospitals' erasure at the end of the war, as each one closed down and sent its burdens home.

Notes

This essay was first published in Civil War Washington: History, Place, and Digital Scholarship, ed. Susan C. Lawrence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015). It is reproduced with permission and has been revised and updated for publication here, as described in "Civil War Washington: The City and the Site." The copyright to this essay is held by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska, and Civil War Washington's Creative Commons license does not apply to it.

- "The Infirmary," Washington Evening Star, May 21, 1861; "The Army Hospitals," Washington Evening Star, August 14, 1861. I am enormously grateful to Kenneth J. Winkle for his generosity in extracting and sharing articles on hospitals in Washington from the city's newspapers for the period of the Civil War. I also thank Kenneth M. Price for his comments on an earlier draft. [back]

- The medical faculty petitioned the secretary of the interior for compensation "for the use of the Infirmary and furniture, on Judiciary Square, lately destroyed by fire" in May 1862. Charles Smith, Secretary of the Interior, to the Surgeon General's Office, May 20, 1862, NARA RG 112, Surgeon General's Office, Registers of Letters Received, vol. 14, January 16, 1862, to December 11, 1862; "The Army Hospitals," Washington Evening Star, August 14, 1861. Charles Rosenberg, The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America's Hospital System (New York: Basic Books, 1987), 100–107, provides the general context for American hospitals at this time. [back]

- Mary C. Gillet, The Army Medical Department, 1818–1865 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1987), 114–22. [back]

- Americans based their military medical service on the British model. See J. G. V. Milligen, The Army Medical Officer's Manual upon Active Service (London: Burgess and Hill, 1819), 58–122. [back]

- Florence Nightingale, Notes on Hospitals (London: John W. Parker and Son, 1859); G. C. Cook, "Henry Currey, Friba, 1820–1900: Leading Victorian Hospital Architect and Early Exponent of the 'Pavilion Principle,'" Postgraduate Medical Journal 78 (2002): 352–59. [back]

- Susan C. Lawrence, "Organization of the Hospitals in the Department of Washington." [back]

- Charles Janeway Stillé, History of the United States Sanitary Commission, Being the General Report of Its Work during the War of the Rebellion (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1866), 93–95. Not everyone was thrilled with the prospect of having large hospitals built right in the city, as Armory Square, Judiciary Square, and the Lincoln were. The "citizens of Washington" petitioned the Senate "for the sake of the soldiers and citizens, to prevent the construction of wooden buildings for hospitals in the centre of the city, and that the location of such buildings may be selected with regard to the health of the city" in February 1862. Journal of the Senate of the United States, February 20, 1862. Further evidence of citizens' reluctance to support a proposed hospital's location survives in a note about "a Petition of Citizens of Washington DC, against the location of Military Hospitals in Judiciary Square," transferred from the War Department to the Surgeon General's Office in early March 1862, Entry in the Register of Letters Received, vol. 14 (January 16, 1862, to December 11, 1862), RG 112, Records of the Surgeon General's Office. I was unable to locate the actual letter referenced in this letter in either RG 112 or the correspondence of the War Department. [back]

- "Another Hospital," National Republican, September 18, 1862. The Lincoln opened on December 23, 1862. [back]

- Data on the number of hospital beds from October 1862 to April 1865 are derived from RG 94, Records of General Hospitals. [back]

- Surgeon Charles S. Tripler, when medical director of the Army of the Potomac from July 1861 to July 1862, begged that hospitals with twenty thousand beds be constructed in Washington. He had a plan for very plain barracks-style wooden buildings that could go up for an estimated $25 per bed. The design provided by the U.S. Sanitary Commission cost $75 per bed, which Tripler got down to $60 per bed. The surgeon general approved funds for approximately five thousand. Charles S. Tripler, "Report of the Operations of the Medical Department of the Army of the Potomac, from Its Organization in July, 1861, until the Change of Base to the James River in July, 1862," in the MSHWR, pt. 1, v. 1, appendix XLV, p. 51. [back]

- "Character of the American Soldier," Daily Morning Chronicle, November 6, 1863; "Care for the Wounded," Daily Morning Chronicle, June 7, 1864; Amanda Akin claimed that Armory Square was built under the direction of Dr. Bliss, at the request of the president for "one as complete and comfortable as could be devised." According to her recollections, Lincoln frequently visited the hospital, implying that it was his favorite. Amanda Akin Sterns, The Lady Nurse of Ward E (New York: Baker and Taylor, 1909), 7–8. [back]

- "Interesting Anniversary Exercises at Armory Square Hospital," National Republican, August 10, 1863; "Presentation," Daily Morning Chronicle, January 21, 1864; "Amory Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, April 27, 1864. [back]

- "The Army Hospitals," Washington Evening Star, August 10, 1861; "New Hospital," Washington Evening Star, September 2, 1861; "Another Military Hospital," Washington Evening Star, September. 10, 1861; Louisa May Alcott found that the Union Hotel Hospital reeked with "the vilest odors that ever assaulted the human nose," although she was reacting as a new nurse. Her comment does cast some doubt on the quality of the hospital's ventilation. Louisa May Alcott, Hospital Sketches (Boston: James Redpath, 1863), 33. [back]

- "Campbell Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, January 26, 1863; "Campbell Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, March 20, 1863; "Columbian College Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, February 21, 1863; "Douglas Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, November 22, 1862; "Douglas Hospital," National Republican, January 14, 1864. For other laudatory reports, see "Eckington Hospital," National Republican, July 16, 1862. [back]

- "Patent Office Hospital," National Republican, September 23, 1862; see also "The Capitol Hospital," National Republican, September 3, 1862. [back]

- Ernest Furgurson, Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War (New York: Knopf, 2004), 183. The secretary of war was so irritated with Trinity Church that he ordered that it not be closed when other churches were being returned to their congregations. Abbott to Hammond, January 16, 1863, in Letters Received January 3, 1862, to March 27, 1863, Letter "A" RG 112 Office of the Surgeon General, NARA. [back]

- "The Tender of Union Chapel Accepted," National Republican, June 21, 1862; database entry "Union Chapel General Hospital." [back]

- "Another Church Offered," National Republican, June 30, 1862; "E Street Baptist Church," National Republican, June 25, 1862. [back]

- George M. Anderson, S.J., "Bernadine Wiget, S.J. and the St. Aloysius Civil War Hospital in Washington, D.C." Catholic Historical Review 76 (1990): 734–64; "Taking Churches for Hospitals," National Republican, July 1, 1862; "More Church Hospitals," National Republican, September 11, 1862. [back]

- "Churches Given Up," National Republican, December 8, 1862; "Church Reopened," Daily Morning Chronicle, February 17, 1863. For the number of churches and the number of churches used as hospitals, consult the database. [back]

- Examples of such letters are scattered throughout the correspondence of the Surgeon General's Office in RG 112, Records of the Surgeon General's Office, NARA. [back]

- "The Horrors of the Alexandria Hospital," National Republican, February 3, 1862; "The General Hospital at Alexandria," National Republican, February 4, 1862; "Condition of the Alexandria Hospital," National Republican, March 18, 1862; see also "Order Concerning Convalescent Soldiers," National Republican, July 7, 1862. [back]

- "Who Is to Blame?" National Republican, May 21, 1862; "Condition of the Hospitals," National Republican, September 17, 1862; "Report on Hospital Abuses by a Special Committee Appointed by the General Relief Association," National Republican, September 19, 1862; "Malappropriation of Hospital Stores," National Republican, September 10, 1862; John R. Brumgardt, ed., Civil War Nurse: The Diary and Letters of Hannah Ropes (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1980). [back]

- "The Hospitals," National Republican, January 31, 1863; "Hospital Abuses," National Republican, October 3, 1862. [back]

- "To the Union Ladies of Washington and Georgetown," National Republican, June 9, 1862. [back]

- "Why Does the Sanitary Commission Need So Much Money?" Daily Morning Chronicle, January 26, 1864; Stillé, History of the United States Sanitary Commission, 19, 33–38. [back]

- New Hallowell General Hospital in Alexandria was one officers' hospital; another was the Park Hospital, albeit only from July to September 1862; a third was the Seminary Hospital in Georgetown (database entries: search on "officers" in "places"). A report on May 19, 1864, noted that the Mansion House Hospital (First Division Hospital) in Alexandria had special wards dedicated to officers, separate from the enlisted men's wards; "Wounded Officers from the Late Battle," National Republican, August 8, 1862; "Sick and Wounded Officers," National Republican, January 2, 1863; "Wounded Officers Reported at Surgeon Antisell's, June 23," Daily Morning Chronicle, June 24, 1864. But also see "Arduous Responsibility," Daily Morning Chronicle, June 24, 1862, for an account of General Connor's condition at Douglas Hospital. [back]

- Rosenberg, Care of Strangers, 22, 45, 50–51, 104–6. [back]

- "Music for Hospitals," Daily Morning Chronicle, December 1, 1862; "Concert at Lincoln Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, May 7, 1864; Amanda Akin Sterns, in her The Lady Nurse of Ward E (New York: Baker & Taylor, 1909), frequently mentions music and singing as a feature of ward life in Armory Square, which was encouraged in order to keep the patients' spirits up. See also Walt Whitman, Memoranda during the War (1875), 21–22. [back]

- M. Hamlin Cannon, "The United States Christian Commission," Mississippi Valley Historical Review 38 (1951): 61–80. [back]

- "Spiritual and Intellectual Condition of the Patients in Carver Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, January 18, 1863, emphasis original. For a discussion of the role of poetry in three Washington hospitals' newspapers— themselves a source of moral uplift—see Elizabeth Lorang, "'Not feeling very well...we turned our attention to poetry: Poetry, Washington DC's Hospital Newspapers, and the Civil War" in Literature and Journalism: Inspirations, Intersections, and Inventions from Ben Franklin to Stephen Colbert, ed. Mark Canada (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2013). [back]

- "A Good Thing for the Hospitals," National Republican, April 20, 1864; "Campbell Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, February 5, 1864; "Literary Exercises in Hospitals," National Republican, February 5, 1864. [back]

- Jane E. Schultz, Women at the Front: Hospital Workers in Civil War America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004); Deborah Judd, Kathleen Sitzman, and Megan Davis, A History of American Nursing: Trends and Eras (Sudbury MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2010); Susan Reverby, Ordered to Care: The Dilemma of American Nursing, 1850–1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987). [back]

- Brumgardt, introduction to Civil War Nurse, 29–36; "Employment of Women as Nurses in the Army Hospitals," Washington Evening Star, June 11, 1861. See also Thomas J. Brown, Dorothea Dix: New England Reformer (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1998). [back]

- See, for example, Extracts from the Muster Roll of Douglas Hospital, October 1861 to October 1863 DC Register 317 of RG 94 Field Records of Hospitals. This roll shows the names and pay of men employed as nurses. [back]

- "To the Ladies of Washington," Washington Evening Star, May 20, 1861."[back]

- "Good Samaritans," Washington Evening Star, July 25, 1861; "Good Samaritans," Washington Evening Star, July 25, 1861; "Not So," Washington Evening Star, August 6, 1861; Furgurson, Freedom Rising, 122–24. [back]

- "To the Union Ladies of Washington and Georgetown," National Republican, June 9, 1862. [back]

- "An Appeal," and "Who Will Respond?" National Republican, September 1, 1862; "Large Number of Wounded Arrived," "Who Will Aid?" "Aid for the Wounded," and "All Honor to the Ladies of the Seventh Ward," National Republican, September 3, 1862. [back]

- "Thanksgiving, How It Was Celebrated Yesterday: The Observance in the Hospitals," Daily Morning Chronicle, November 28, 1862. [back]

- "To the Public," Daily Morning Chronicle, December 5, 1862. [back]

- "Great Meeting of Ladies at the Patent Office—Christmas Dinner to the Sick and Wounded," Daily Morning Chronicle, December 18, 1862. [back]

- "The Fourth at the Hospitals," National Republican, July 6, 1863; "Thanksgiving Day at the Hospitals," Daily Morning Chronicle, November 24, 1863; "Thanksgiving at the Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, November 25, 1864. [back]

- "The Grand Levee," Daily Morning Chronicle, February 11, 1863; see also "'Hop' at the Stanton Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, March 16, 1865. [back]

- "The Grand Torchlight Procession," National Republican, October 22, 1864; "A New York State Agent in Search of McClellan Voters," Daily Morning Chronicle, October 11, 1864; "Grand Gathering of the Military and Civilians at Armory Square Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, October 11, 1864. [back]

- "After the Battle," Daily Morning Chronicle, May 21, 1864. [back]

- Journal of the Senate, July 19, 1861. [back]

- Congressional Globe, July 19, 1861. [back]

- Stillé, 307–10. For the process of making inquiries, see "To All Who Have Friends in the Army," National Republican, February 26, 1863. [back]

- See, for example, "The Losses," National Republican, September 6, 1862; "The Roll of Honor: The Names of the Wounded," Daily Morning Chronicle, May 12, 1864. [back]

- Letter from J. J. Woodward to Surgeon General Hammond, November 12, 1862, on the "neglect of the majority of medical officers with regard to the monthly reports of sick and wounded," RG 112, Surgeon General's Office Correspondence. [back]

- Men in regiments first saw their regimental surgeon, who sent them to the post hospital if they were too sick to stay in quarters. Those with serious illnesses and injuries were then transferred to a general hospital, although there were likely exceptions to this generalization. In theory, it would be possible to study surviving registers of the sick and wounded for post hospitals in order to determine what proportion of the regiment were, on average, patients in them on a daily basis, and so to calculate ballpark figure for how many sick and injured should be estimated for the Defenses of Washington. This suggestion is based on an examination of Virginia Register 620, Sick and Wounded, Post Hospital Forts Allen and Marcy, June–October 1864, RG 94, Records of the Adjutant's Office, Entry 544 Field Records of Hospitals. It shows the sick regularly being transferred to general hospitals, which means they were included among the institutions for which we have data. The volume also includes morning reports that the regimental surgeon made. [back]

- E. P. Vollum, "Report on the Transportation of the Wounded after the Battle of Gettysburg," MSHWR, pt. 1, v. 1, appendix 132, p. 144. [back]

- For notices that wounded were being moved out, see "Six Car Loads of Invalid Soldiers," Washington Evening Star, September 14, 1861; "Sick and Wounded Soldiers Sent Away," National Republican, September 11, 1862; "Convalescents," National Republican, June 17, 1863. [back]

- "Soldiers in Hospital," Daily Morning Chronicle, November 11, 1862. [back]

- Benjamin Franklin Cooling, Symbol, Sword, and Shield: Defending Washington during the Civil War (Shippensburg PA: White Mane, 1991), 106, 109–10, 125. There were varying numbers of troops in camps around the District at different times during the war, so it may be possible that there were other sick in camp hospitals, but not enough to total 28,500 for the Department of Washington on any one day. [back]

- Walt Whitman, Memoranda during the War, 26. [back]

- For example, see Kathleen W. Dorman, "'Interruptions and Embarrassments': The Smithsonian Institution during the Civil War," archived in the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine from the Smithsonian Institution's website. She states that there were "56,000 sick and wounded soldiers" in Washington's hospitals in the fall of 1862. Unfortunately, the source reference for this part of the essay has been lost. The number may have its origins in a table published in the MSHWR, pt. 1, v. 1, appendix 82, p. 98. This table, included in Jonathan Letterman's "Extracts from a Report of the Operations of the Medical Department of the Army of the Potomac from July 4th to December 31st, 1862," notes that 56,050 patients had been in the hospitals of the Department of Washington from August 31 to December 31, 1862, a period of four months. There were 11,797 in the hospitals on August 31 and 12,932 remaining on December 31, but not 56,000 on a single day. [back]