Washington, the Symbolic Capital

Surrounded by Confederate armies in Virginia and southern sympathizers in Maryland and lying just one hundred miles from the Confederate capital, Richmond, Civil War Washington was a beleaguered island of nationalism amid a sea of disunion. At the outset of the war, the federal government’s hold on Washington was so precarious that Abraham Lincoln had to enter the city by night, wearing a disguise, to lay his claim to the contested presidency. Soon, he arrested the mayor for disloyalty, declared martial law to keep the railroad running to Baltimore, and stood in the window of the White House watching as a Confederate flag waved in Alexandria just across the Potomac. During four years of war, Confederate armies threatened Washington repeatedly and, during the summer of 1864, actually attacked the city. By the end of the Civil War, however, Washington had emerged as the paramount symbol of national unity—as well as freedom and equality—that it remains to this day.

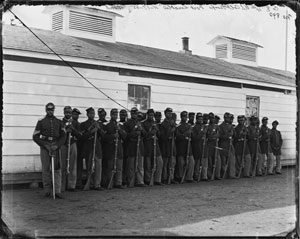

The struggle to defend this beleaguered city and, more than that, to transform it during four tumultuous years into a symbol of national unity and resolve, rested with the thousands of soldiers who defended the city, many of whom died and lie buried there, the fugitive slaves who built the “freedom villages” and later joined the Army, the volunteers who tended the wounded in temporary hospitals after each military engagement, and all of the city’s people who sacrificed in one way or another to support the war effort. Among the more conspicuous visionaries who viewed Washington as more than just another American city were Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman.

The struggle to defend this beleaguered city and, more than that, to transform it during four tumultuous years into a symbol of national unity and resolve, rested with the thousands of soldiers who defended the city, many of whom died and lie buried there, the fugitive slaves who built the “freedom villages” and later joined the Army, the volunteers who tended the wounded in temporary hospitals after each military engagement, and all of the city’s people who sacrificed in one way or another to support the war effort. Among the more conspicuous visionaries who viewed Washington as more than just another American city were Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman.

Lincoln envisioned Washington as a key symbol of the American nation, and he worked diligently to turn that idea into a reality. He left Washington just a handful of times, to meet with his generals in the field, to speak at Gettysburg, and finally to tour the devastated city of Richmond after its surrender. Committed to Washington, he authorized a ring of sixty-eight forts and twenty miles of trenches to defend it, and when Jubal Early raided Washington in 1864, he stood on the battlements to observe the action. Within these fortifications, Lincoln was the focus of the city as he led the war effort, marshaled support for the Union, and projected both real and symbolic national leadership. He literally rallied the troops, met White House visitors by the thousands, comforted wounded soldiers in hospitals and consoled their families in eloquent letters, patronized the theaters to help maintain morale, and insisted that public improvements proceed. Through his very accessibility in the wartime city, he put his own life at risk to set the right example. By the end of the war, he had helped transform Washington into a truly national capital. Most visibly, Lincoln insisted that work continue without interruption on the unfinished dome of the Capitol building, as the symbol of democracy–“government by the people.”

Following the battle of Fredericksburg, Walt Whitman traveled to northern Virginia because he feared that his brother had been wounded in battle. Finding that George Whitman had suffered only a superficial face wound, Walt turned his attention to other soldiers, helping to transport them to hospitals in Washington, DC. He then stayed on in the city to minister to thousands of other wounded soldiers. His voluminous writings during his time in Washington provide an extraordinarily powerful record of the Civil War years and offer a unique perspective on the heroism and sacrifice during this defining period of American history. In letters, poems, journalism, and manuscript drafts, Whitman speaks powerfully about the full range of issues that divided Americans, especially race and slavery. Whitman himself once claimed of Leaves of Grass, the first masterpiece of American poetry, that “my book and the war are one,” and this is true insofar as the book was radically altered by the war just as the nation was. Yet his published poetry is only a small fraction of his Civil War account, which has never before been collected and organized. With an ordinary man’s vantage point on the war and an extraordinary artist’s sensibility, Whitman focused on what often escaped attention: the war experiences of the common soldier, the stoicism and heroism of ordinary individuals, and—above all—the suffering, dignity, and enormous courage he saw in his hospital visits to approximately 100,000 wounded men, Northerners and Southerners alike.

Here, and at this time, Lincoln the statesman and Whitman the poet crossed paths briefly in their common effort to bring out the best in their nation and understand the sacrifices that they witnessed every day around them. “I see the President almost every day,” Whitman wrote, and he observed that the president “dress’d in plain black, somewhat rusty and dusty; wears a black stiff hat, and looks about as ordinary in attire, &c, as the commonest man.” For Whitman, as for other Americans, the simple but always imposing figure of Lincoln symbolized the dedication, compassion, and commitment to democratic principles that guided the Union war effort to its ultimate victory. The two men never met but shared the burdens and the blessings of life in the nation’s capital during the drawn-out civil war, as well as the idealism that remade the nation and its capital and made that struggle worth the sacrifice. Indeed, Whitman could have been describing this American Iliad, the story of the nation’s capital under siege, when he concluded his tribute to Lincoln’s wartime leadership, “O Captain! My Captain!,” with the exultant lines, “The ship is anchor’d safe and sound, its voyage closed and done;/From fearful trip, the victor ship, comes in with object won.”