Washington, the Strategic Capital

Situated in the midst of the Eastern Theatre of war and sandwiched between two slave states, Washington, DC, held tremendous strategic, political, and moral significance for both the Union and the Confederacy. Strategically, Washington was the greatest military target and potential prize for Confederate armies, just as capturing Richmond remained the Union's primary military goal throughout the war.

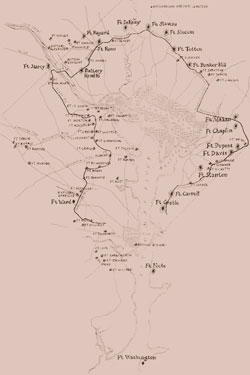

From the First Battle of Bull Run onward, Confederate armies continually threatened Washington as part of General Robert E. Lee's strategy of "taking the war to the enemy." Lee's summer offensives of 1862 and 1863, which culminated in the turning points of Antietam and Gettysburg, were primarily designed to threaten Washington, encourage southern sympathizers in the North, and challenge the Lincoln Administration's authority to govern. At Lee's behest, Stonewall Jackson's army could emerge from the Shenandoah Valley and advance on Washington whenever the Army of the Potomac neared Richmond. As a result, Lincoln was insistent on maintaining an army of 15,000 to 50,000 men around the capital, which denied needed manpower to the Union offensives. During the winter of 1861-62, after the First Bull Run scare, Congress began constructing a 37-mile ring of fortifications around Washington. The defensive system eventually included sixty-eight forts connected by twenty miles of trenches. Ninety-three artillery positions boasted 800 cannons. By the end of the war, Washington was the most heavily defended city on earth. During the summer of 1864, Confederate General Jubal Early led a raid on the city that tested its defenses and rallied its residents, including President Lincoln, who rushed to Fort Stevens to witness the repulse of the enemy army.

From the First Battle of Bull Run onward, Confederate armies continually threatened Washington as part of General Robert E. Lee's strategy of "taking the war to the enemy." Lee's summer offensives of 1862 and 1863, which culminated in the turning points of Antietam and Gettysburg, were primarily designed to threaten Washington, encourage southern sympathizers in the North, and challenge the Lincoln Administration's authority to govern. At Lee's behest, Stonewall Jackson's army could emerge from the Shenandoah Valley and advance on Washington whenever the Army of the Potomac neared Richmond. As a result, Lincoln was insistent on maintaining an army of 15,000 to 50,000 men around the capital, which denied needed manpower to the Union offensives. During the winter of 1861-62, after the First Bull Run scare, Congress began constructing a 37-mile ring of fortifications around Washington. The defensive system eventually included sixty-eight forts connected by twenty miles of trenches. Ninety-three artillery positions boasted 800 cannons. By the end of the war, Washington was the most heavily defended city on earth. During the summer of 1864, Confederate General Jubal Early led a raid on the city that tested its defenses and rallied its residents, including President Lincoln, who rushed to Fort Stevens to witness the repulse of the enemy army.

Within this fortified ring sat a city of 63,000 people, America's twelfth largest in 1860. Between 1860 and 1870, Washington doubled in size, experiencing the greatest growth in its entire history. During the war, the city filled with people and at times swelled to 200,000. Union armies, composed of volunteers and draftees from across the North, moved continually through the city, up to 140,000 at a time. Forty thousand fugitive slaves, known as "contrabands," fled to the nation's capital, occupied camps run by the government and private charitable organizations, and worked on military projects. Thousands of them joined the Union Army after Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation allowed them to enlist. Newspaper correspondents from across the U.S. and Europe, foreign dignitaries and military observers from around the world, and tourists by the thousands crammed the hotels and sought entertainment in the theaters, music halls, and saloons that proliferated during the war. Confederate deserters, opportunists of all varieties, including spiritualists and prostitutes, and clandestine rings of southern spies and assassins abounded.

Above all, the city filled up with wounded soldiers in the wake of every major military engagement in the Eastern Theatre. At the beginning of the war, makeshift hospitals ministered to the wounded, more than 56,000 soldiers during the first year alone. Midway through the war, more sanitary "pavilion" hospitals—about thirty of them—each with ten or twelve wards housing 600 patients, dotted the city. Volunteers from across the North, including Clara Barton, Louisa May Alcott, and of course Walt Whitman, tended to the wounded, and President Lincoln and his wife Mary visited frequently. Those who died were buried in pine coffins at a cost of $4.99 in the Soldiers' Home Cemetery. When it filled up in 1863, the government seized Robert E. Lee's estate across the Potomac River in Arlington, Virginia. Coffins moved solemnly, by the hundreds, across the Long Bridge and over the Potomac to what became Arlington National Cemetery, perhaps the nation’s greatest symbol of military honor and sacrifice.

With the outbreak of war, the Union transferred its military headquarters to Washington from West Point, New York. The War Department, the Navy Department, the Union Army Headquarters, the Army of the Potomac Headquarters, and the Headquarters Defenses of Washington all sprang up within walking distance of the White House. Abraham Lincoln frequented them personally to oversee the war effort. Washington also housed the largest arsenal in the Union at what is now Ft. McNair, as well as the U.S. Navy Yard and the Baltimore and Ohio railway depot, which moved thousands of troops into and through the city daily. Washington served as the main supply depot for the Army of the Potomac, which required 10,000 soldiers and civilians to supply it. South of the White House, the mall around the unfinished Washington Monument contained a cattle grazing area and slaughterhouses to feed the armies that defended the city. Washington also maintained an array prisons for captured Confederates and disloyal northerners. The Old Capitol Prison, the largest, sat across the street from the Capitol building and held over 2,700 prisoners at its peak. With its ebb and flow of armies, its sprawling defenses, and its overflowing hospitals, hotels, theaters, prisons, and cemeteries, Washington was a focal point of the war, as well as a microcosm of wartime America.